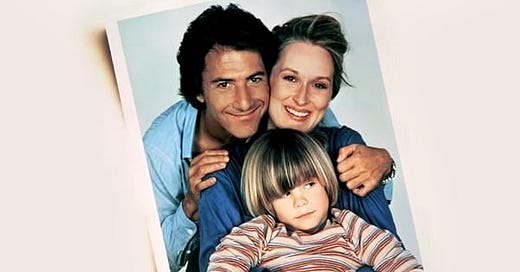

Film: Kramer vs. Kramer (1979)

Screenplay by: Avery Corman, Robert Benton, Meryl Streep (based on the novel by Avery Corman)

Directed by: Robert Benton

Starring: Meryl Streep (Joanna), Dustin Hoffman (Ted), Justin Henry (Billy), Jane Alexander (Margaret Phelps, the friend)

Dear Divorcees, Single Parents, Couples, and Jaded Romantics,

In Shakespeare’s play Macbeth, the way that Lady Macbeth keeps her husband under her thumb is by questioning his manhood. She keeps talking about courage, and telling him he needs to be courageous. Her idea of manly courage is that he take some risks—however, the specific risks she insists upon are that Macbeth get his hands bloody with murder, corruption, and manipulation in order to gain power.

There are three witches in this play of Macbeth, and there is a question whether the witches set something in motion, just by giving voice to it—or if Macbeth would have headed in his tragic trajectory to begin with.

When I saw a performance of Macbeth in the last year, at a local theater in Philadelphia, the director had decided to cast all the parts as men, in “traditional” Shakespeare form. A woman I knew was very upset because she felt that this production excluded women from a play where women characters had a lot of authority and power. Yet when I watched the all-male cast—many members in drag, basically, with gaudy lipstick—I loved it. I thought it worked extremely well, and I felt even more the manipulative tactics of Lady Macbeth, because her approach to telling Macbeth what to do had that deeper, more masculine intonation.

It was also really fun to watch men make out on stage under the guise that they were heterosexual couples. That just throws all of our country’s weird obsession with sexual orientation out the window and shows you that love is love, acting is acting. Infatuation is infatuation. Deceit is deceit. It don’t matter if you’re a girl kissing a girl, or a boy kissing a boy.

In Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), Joanna and Ted get divorced, and the gender roles of man and woman are explored and discussed as part of the plot. Unlike Lady Macbeth, Joanna (played by Meryl Streep) has no interest in power, control, or domination of her husband. She is just an unhappy woman trying to stay alive in a domestic situation that doesn’t work for her. She is capable of making just as much money as Ted (Dustin Hoffman), if not more. But when she becomes a mother and desires a career as well, Ted negates her career ambitions, her concerns and wishes, and he adheres to his traditional gender mentality of “man as breadwinner,” “woman as domestic servant and supporter.”

Until Joanna leaves him. Then, Ted has a whole new set of understandings that bypass his ideologies about gender norms. He is more in tune with his sensitive side—making breakfast and dinner, watching his son on the playground, missing deadlines at work so that he can take his kid to the doctor. He has to do all the things that women traditionally do. And he loves it so much, he wants to keep doing it. He realizes that raising his son is what makes him happy—not his career.

If Joanna had suggested to Ted that he prioritize child-rearing instead of his job, and she be the one to go to work full-time and focus on career advancement, he surely would have said no. But the shock of her abandonment requires him to adapt and to finally understand. Absence makes the heart grow fonder, perhaps? Absence teaches a person things. Absence finally makes someone hear what they never could hear.

For a long time, the inner longings, ambitions, woes, and psychic landscape of women—energetically, artistically, and mentally—was not accepted as equal in worth to the “universal human experience,” which is so often viewed as male. I remember some dudes in college writing courses I taught, getting annoyed when I presented literature or nonfiction by women authors who had some “beefs” with the way things were happening in culture and beyond. I could see the white guys shrinking in their chairs, like, “Oh jeez, here we go again with this bullshit.”

Why? I always wondered. A woman is your sister, your aunt, your mother, your grandmother, and if not now—then in the future—your daughter. Why are the words, visions, perceptions, experiences of women not also universal? Women’s lives certainly have universal impact.

I have perceptive abilities that annoy people, so I often keep my knowings quiet, but I knew what bugs were probably up these young dudes’ butts. Many young men see women as objects of desire only, until forced to open their minds a bit more. Women are something to be acquired—like nature, like land, like investments, like stocks, like money, like praise—which means women’s personal opinions and experiences may be simply annoying. (Women in moving-images on secret-screens tend to be way more accommodating and eager to please than real-life women.) If a younger man wants to be king of his castle, a woman’s differing opinion or experience may just get in the way of his approach or expectation for living. That is, unless he has a role model of a mom or other women in his community that teach him the value of a multi-faceted feminine point of view.

This inability Ted has to accept the feminine point of view seems to be why Joanna leaves him, and why this movie Kramer vs. Kramer made such a cinematic historic impact in showing a loving, caring father who is able to find the mother inside himself. Oh, if only we had more Dustin Hoffmans in the world, to show us the soft, grounded father figure! Dustin, with his tenderness, his richness, his earthiness! Dustin, with his cute dimples, his cocked hips, his elasticity, his steadiness, his quiet and tender masculine soul! Oh em gee, and those cute little Dustin-Hoffman-lips.

Kramer vs. Kramer is, like other “divorce movies,” Ted’s story. Joanna speaks about her emotions and life journeys, and Ted is internally strong enough—over time—to keep loving her in a new way, as the mother of his child, rather than his partner. Yet we don’t actually see or witness Joanna’s story. (Even Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth gets at least one scene where we see her inner life.) We don’t watch Joanna’s adventure out on her own. We don’t experience the emotions with her, of having to leave her family to stay alive and to get healthy, and what it was like to finally begin to stand on her own after years of being negated and unseen, while darkness grew inside her.

I wrote a short story after my own divorce, about a Joanna type of character. It is called “The Voyager,” and it won a short story award the same year I drove cross-country to California. I carried all the doubts and worries with me that Joanna had, and so did my story’s character, Penelope. There are many women who don’t take any voyage, but instead choose addictive behaviors, multiple sexual partners, prescription drugs (or other drugs) and substances, to manage their stress and emotions. There are women who don’t heal themselves, and instead become Lady Macbeths—or scary witches.

A lot of women get fed up as they age. They get sick. They put up with so much, and then they can’t put up with anymore. If a woman is Lady Macbeth, she turns to her shadow side and dictates a man’s every decision, all the while convincing him he is more masculine for listening to her corruptive gestures. If a woman is gentle and kind, she cries a lot. She takes breaks. She gets space where she can get space. She’d rather grieve and weep and heal where no one can see. She’d rather do what it takes to be strong herself, and to be honest and vulnerable in situations that call for it, than to stomp on someone else to move forward in her own life. Those are the Joanna’s.

A lot of women struggle with mental health, and not a lot of us know why, or want to hear or accept the why. Fortunately for this couple in Kramer vs. Kramer, and their little boy, Billy, there is enough forgiveness, good nature and good will, to put the past slights aside and focus on the good of the future. But in many instances after broken relationships, women and men don’t heal. The reason may be that we are so out of tune with nature, with natural rhythms of how to exist, with cycles and renewal. Women are more vocal about their mental health issues, perhaps, because our bodies are naturally made to be in tune with seasons and nature. We ovulate, we shed, we start again. We are consistently aware of the different phases our body goes through, related to reproduction and life, and giving birth. Like the ocean, our moods may even be naturally connected to the phases of the moon. Capitalistic lifestyles, however—production, industry, government, processing, militaristic endeavors—do not often honor feminine nature, and it is why we see so many people out of balance and turning to various forms of consumption to keep up appearances. We see people die before they have to die. We see people lose their souls.

Joanna is a powerful feminine character because she does not deny her own vulnerability or her mistakes, and she quietly clings to her convictions. She openly admits her struggles in self-esteem, and the way her decisions were dictated by her too-tiny sense of self, rather than the strength she did actually have within—when she was allowed to blossom.

Ted has to learn the power of softness and sacrifice as he becomes father and mother to his son. His guru is not his boss at work, but his kid. And through this disjointedness and fragmented-ness he never would have willingly chosen—divorce—the man and woman in the film become true equals.

Kramer vs. Kramer is streaming now on Amazon Prime and elsewhere. It is one of the best studies in acting you will find in film. It is also a great story of family.

Hugs,

Ms. Wonderful

Digital Spotify playlist about marriage, divorce, and relationships: “I Said, ‘I do’”

And speaking of families and divorce, mark your calendar to come see my one-act play for the Philadelphia Fringe Festival—”Family Law Comedy Special”—September 6th and 7th at Yellow Bicycle Theater. With the purchase of a ticket, each person gets a free meditation class. More details coming in July. (This play is much funnier and happier than Kramer vs. Kramer.)

The title of this Ms. Wonderful post—“Divorce, Thy Name is Woman”—is a poem by confessional poet Anne Sexton, which you can read here.