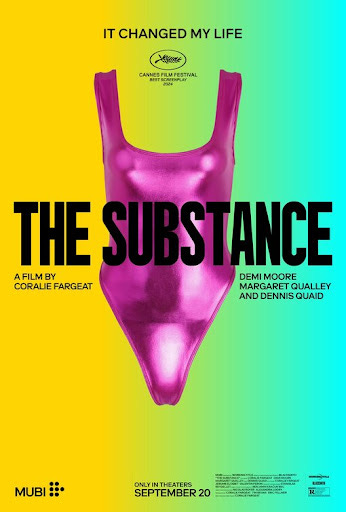

Film: The Substance (2024)

Written and Directed by: Coralie Fargeat

Starring: Demi Moore, Margaret Qualley, Dennis Quaid

Dear Women in Film and Women Who Watch,

I watched The Substance. I did a healing session and then I got that little dropdown menu in my brain about this film, and so I rented the thing. I felt it was time to face it.

It’s wild. I was watching it and utterly fascinated until I fell asleep. (I take two days to watch movies. Sometimes, three. Especially if I start watching something at night.)

And here is what I think about good movies—movies I want to watch again and again. Movies that touch me and sing and plant a big rosebush in my heart. There is something potent in the scenes, and between the people. Something happens in the relational dynamics of scenes that I don’t forget.

This film, The Substance, is more a movie about a woman’s relationship with herself, and that relationship with herself is one of hatred. The premise is very universal, but many people may not recognize it. And inside this war-within-mentality, is convergent metaphors of giving birth, and the truth of manifestation, and what we give birth to. (It’s so Frankenstein.) This woman, Elizabeth Sparkle, essentially gives birth to a younger version of herself—Sue—who despises her, uses her, abuses her, and tries to destroy her—all so that she can stand on a stage and have people clap for her.

I don’t vibe with this thing. If I try, I can turn it on all its angles and find my way in. I can say that the writer/director Coralie Fargeat is like a female version of Aronofsky, or Lynch—remember Black Swan? And Mulholland Drive? What style this film has. The women in those male-auteur films had some demons and shadows too, but we didn’t see the demons come out so “boldly.” I can stand up for Coralie Fargeat and even stand up for Demi Moore, because Demi lost the Oscar to that young woman actress from Anora who looked an awful lot like Margaret Qualley’s character Sue—and that hurt my heart, to see Demi lose like that, the camera rushing so quickly to her face, to make sure her reaction to the loss was “just-so.” Personally, I like seeing older women lifted up. (I have not seen the movie Anora.) But beyond the politics and the way things are “supposed to be,” and the way I am “supposed to feel about women and women in leadership in film and beyond,” I just found that The Substance put too much emphasis and power on a guy in a suit. Harvey—the TV tycoon—is well-played by Dennis Quaid, and he is loud and obnoxious and wants what he wants, and eats shrimp or crabs (I couldn’t tell which) in this really gross way. But is the ethos of the film any different than the character of Harvey, who we’re supposed to hate? Does one person acting out, or being grotesque, have to top the other grotesque person? What kind of game are we playing here? The grossest person wins? The biggest “F-you!” wins?

That’s rather adolescent of the whole movie and move premise, I surmise.

When I was in college, my friends put on a production of this play called “The Most Massive Woman Wins,” by Madeleine George.

I was introverted in college, and I preferred my head to be always buried in a book, and my main extroverted outlet was having a radio show to play music because people couldn’t see me behind their radios, and I—like many adolescents—didn’t like my body. My body felt like one thing, and I a separate entity. I had a couple of friends who loved being in theater, and sometimes got me to join, but mostly, I was writing short stories and hiding because I didn’t want to be that seen.

Yet this play my friends performed—”The Most Massive Woman Wins”? This play spoke to me in a really big way. This play enthralled me.

The women on the stage were talking about radishes a lot. There was some theme about mythology, and radishes, and hunger, and desire. What was desire? At 18, 19, 20, and beyond, I was not sure what "desire” was. I only had watched a ton of movies and music videos, and perused a bunch of magazines, telling me that it was my job “to be desired.” And I was fighting that and trying to fulfill it.

Could I actually have something inside me come forth and assert itself in my lifetime, rather than have others asserting their wills, desires, and assumptions upon me?

Hmm. That was an interesting question, and the play posed it. The four women on the stage danced with it, and discussed stories and legends, and their secret yearnings.

More hmm. As a woman, I was allowed to want things? This was the late 90s and early aughts, and I had such low expectations for my life, other than needing to have a steady job and a steady paycheck when I got out of school. But what if there was another space in the paradigm—a liminal space I could step into, an imaginative space, where I had complete freedom to choose my way, rooted in a knowing or a truth inside me, rather than ideologies thrust upon me?

Hmm. More hmm.

I don’t want to give the end of the play away, but I will, because it is the whole point. The women stand on stage at the end, in their underwear. These were my friends, who performed, and who stood. Their bodies were not perfect. I knew their doubts and fears and flaws, and the things they worried about, and the things they wanted or thought about, and what they ate for lunch, and what they thought of our professors, and how late their 10-page papers were after the due date. Still, for the purpose of this play, they took off their clothes and stood in their underwear, unashamed, letting their belly fat show, or the extra flab on their thighs, and they faced the audience. And I burst into tears. I was so moved by the play and its questions, and also by their boldness, and their bravery, and their devotion to their art.

I wish this movie The Substance, had a devotion to life and what is life-giving, and to loving women, the way Madeleine George’s play did. I wish it had the courage my college friends had, back in 1999. Instead, I think The Substance may just be an egotistical mind-game with little sparks here or there of what could be fascinating or fantastic, if the director had more courage to truly explore the issue she pretends to explore. Instead, she just creates grotesquerie and faux-boldness to awe us, the way some dude dropping a bomb is supposed to awe us.

Neither works to heal or help human beings.

(Okay, big boy. What a big, big boy you are, Coralie!)

Vulnerability, and the courage of vulnerability in film can change the leadership of nations, I think.

I’d rather watch a movie by a sensitive man who loves women than this thing that just tells us women are a cog in some warped mindplay, wherein the Harveys are just like the Coralie Fargeats.

(I didn’t like Babygirl, directed by Halina Reijn, either. We can do better than this boring drivel.)

Namaste. Wise Women Win,

Ms. Wonderful

I have made some weird, wild movies over the years. Here is one that is 6 minutes.

Coralie, I love you forgive me, I have to say what’s real.